Product Description

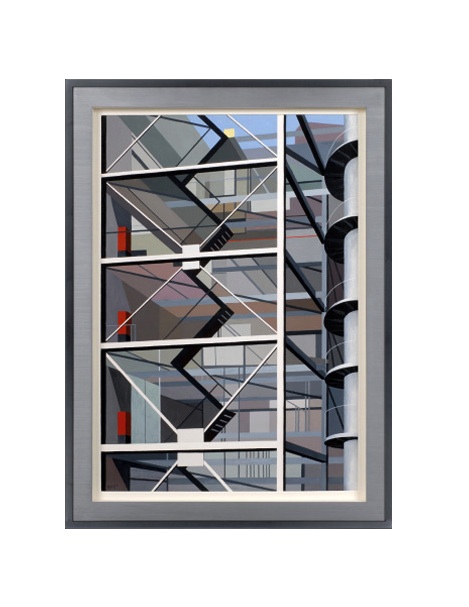

Richard Harold Redvers Taylor, “Modernist building staircase”, Gouache on paper c. 1949

RICHARD HAROLD REDVERS TAYLOR (1900-1975) United Kingdom

Modernist building staircase c. 1949

Gouache on paper, metal and wood frame

Signed: RHRT (lower left)

Marks: Gimpel Fils exhibition label (on back)

Exhibited: “An Exhibition in the Kettle’s Yard Loan Gallery: Sculpture & Painter,

14 February – 10 March, 1972” Gimpel Fils, London

Framed: H: 41 7/16” x W: 30 5/16”

Richard Harold Redvers Taylor (1900-1975) was born in Brighton on March 14th, 1900 and educated at Brighton College and Heatherleys School of Fine Art, Chelsea. His father, Harold Taylor, was a headmaster. Redvers Taylor retired from the Army (where he specialized in topographical surveying in Africa) in 1937 but was recalled for war service. In 1946 he began a new career as a professional painter. Between 1948 and 1958 Taylor was given a series of six one-man shows by Lefevre and Gimple Fils in London. In the 1960’s he turned to sculpture, and in 1972 an exhibition of his sculpture and paintings was held at the Kettle’s Yard Loan Gallery in Cambridge. His work is held in the permanent collection at the Beith Uri V Rami Museum in Israel. Louise Taylor (née Hayden), his wife, was an American and the adopted daughter and heiress of Alice B. Toklas, the companion of Gertrude Stein. Louise Taylor died on 21 July 1977.

Purism, otherwise known as l’esprit nouveau was directly inspired by a spare, functionalist aesthetic and is closely associated with the work of Le Corbusier and his circle in Paris in the second quarter of the 20th Century. In America this purist style was known as Precisionism, which explored similar imaginary during the late 1920’s and 30’s with artists like Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth and Ralston Crawford at the forefront of this movement. In England, the Vorticist movement (1912-1915) was founded by Wyndham Lewis and others and was the precursor to the Purist movement in Great Britain in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Redvers Taylor created geometrical landscapes while reducing volumes to colored planes and outlines to ridges. His artwork combines depth and perspective with flattened cubist fields of color. Architecture of industrial buildings was his favorite subject, whereas people and nature were usually absent from his compositions.

Richard Harold Redvers Taylor, “Modernist building staircase”, Gouache on paper c. 1949

ROBERT BREER (1926-2011) USA

Untitled 1950

Oil on canvas, white-gold leaf and lacquer frame

Marks: Untitled, 1950, Robert Breer, 26×32, No. 29 in a circle (paper label)

Provenance: Robert Breer, Private Collection, Chicago

Canvas: H: 25 3/4” x W: 32”

Framed: H: 32 1/4” x W: 39″

“Breer acknowledges his respect for this purist, “cubist” cinema, which uses geometric shapes moving in time and space”

Robert Breer’s career as an artist and animator spans 50 years and his creative explorations have made him an international figure. He began his artistic pursuits as a painter while living in Paris from 1949-59. Using an old Bolex 16mm camera, his first films, such as “Form Phases”, were simple stop-motion studies based on his abstract paintings.

Breer has always been fascinated by the mechanics of film. Perhaps it was his father’s fascination with 3-D work that inspired Breer to tinker with early mechanical cinematic devices. His father was an engineer and designer of the legendary Chrysler Airflow automobile in 1934 and built a 3-D camera to film all the family vacations. After studying engineering at Stanford, Breer changed his focus toward handcrafted arts and began experimenting with flip books. These animations, done on ordinary 4″ by 6″ file cards have become the standard for all of Breer’s work in fim.

Like many of his generation, Breer did early work influenced by the various European modern art movements of the early 20th century, ranging from the abstract forms of the Russian Constructivists and the structuralist formulas of the Bauhaus, to the nonsensical universe of the Dadaists. As a result of his association with the Denise René Gallery, which specialized in geometric art, he saw the abstract films of such pioneers as Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, Walter Ruttmann and Fernand Léger. Breer acknowledges his respect for this purist, “cubist” cinema, which uses geometric shapes moving in time and space.

In 1955, he helped organize and exhibited in a show in Paris entitled “Le Mouvement” (The Movement), which paved the way for new cinema aesthetics. During this period, Breer also met the poet Allen Ginsberg and introduced him to his film “Recreation” (1956), which made use of frame-by-frame experiments in a non-narrative structure. Although Breer resisted being labeled a beatnik, the film does capture some aspects of beat poetry and music.

When Breer returned to the United States in the late 1950s, the American avant-garde was thriving and films by Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Peter Kubelka and Maria Menken were creating a new visionary movement. Breer found kindred spirits within the New York experimental scene. As Pop Art emerged as a phenomenon in the 1960s, Breer befriended Claes Oldenburg and others. He worked on the TV show, “David Brinkley’s Journal”, filming pieces on art shows in Europe; at the same time, he made his debut documentary on the sculptor Jean Tinguely in 1961.

GALERIE CARREFOUR 141Boulevard Raspail, Paris

Vérité Collection Wood block print poster “ARTS PRIMITIFS, CARREFOUR, 141 BD RASPAIL, DAN 5803″ c. 1948

Float mounted in a finely contoured oak frame.

Inscribed to: A Monsieur E Mme Breton, Vérité Image dimension:

H: 19 1/2″ x W: 12 3/4″

Framed dimension: H: 26 3/4″ x W: 19 3/4”

Price: $9,000

The Vérité Collection of primitive arts started after World War 1 in 1920. Pierre Vérité, a young artist started buying primitive art before anyone else. Vérité opened a small store selling exclusively tribal art in 1931 in conjunction with the Paris Colonial Exposition. Pierre Vérité regarded “primitive arts” as art, and it is the raw power of these primitive pieces that changed the history of 20th-century European culture. In 1936, he opened the Galerie Carrefour on the Boulevard Raspail, which was a hangout for artists and collectors such as Pablo Picasso, Helena Rubenstein, Nancy Cunard and Andre Breton. Tribal art was one of the key influences on Pablo Picasso and he often dropped into Pierre Vérité’s Galerie Carrefour in Paris to buy masks and carvings from Africa and Oceania. Henri Matisse was also a regular visitor, as were other artists such as Fernand Léger and Maurice de Vlaminck, while Vérité used to browse Parisian flea markets with André Breton, Surrealism’s chief theorist. In the decades that followed the opening of the gallery, the Vérité family’s client list grew to include Hollywood stars and leading museum curators, as well as some of the greatest names in 20th-century art. Vérité very quickly became the most important art dealer for primitive arts. In the 1948, Pierre’s son Claude became increasingly involved in the gallery. He went on African expeditions, collecting objects and information, and took photographs to document his travels, while his wife Jeannine was running the gallery operations. With Claude and Jeannine joining the gallery, Galerie Carrefour showed at all “Art Primitifs” exhibitions in Europe and the United States. The gallery established itself as the most important player in tribal arts in the world and exhibited until the 1990’s.