Product Description

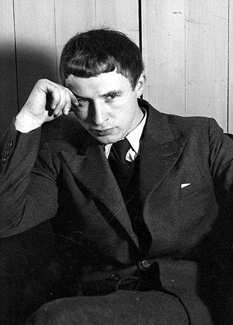

Werner Rohde, Mask, Gelatin Silver Print c. 1920’s

WERNER ROHDE (1906-1990) Germany

Mask c. 1920s

Gelatin silver print

Signed on the back of the photo: Werkbundausstellung “Film und Foto” (typed on label); 9.) 9/ (in ink and red crayon); Kupfer ofun Rourk 60 m R 10.5 x 14.5 cm / ump ubonpposhm bu 6/5 10088 (all in pencil script); fmlg-Rohde Woopswerk (in pencil); Werner Rohde Malen Breuien Oobben 58 (ink script)

H: 21 7/16” x W: 18 13/16” (framed)

Price: $17,500

Werner Rohde’s visual play with the animate and inanimate draws him close to the aesthetics of the surrealists while maintaining a strong alignment with Germany’s new-vision avant-garde. Rohde experimented widely with double exposures, photomontage, perspective and dramatic lighting that reflected his interest in filmic effects. The son of a glass painter (a medium he would turn to later in life), Rohde took up photography during his studies at the Arts and Craft School in Halle. Like Kesting, Willy Zielke and Kretschmer, he participated in the 1929 ‘Film und foto’ exhibition in Stuttgart that remains one of the historical focal points for Germany’s new photographic vision. Despite this early recognition of his work, Rohde fell into obscurity after the war until the rediscovery of his photographs in the mid 1970s. Rohde’s fascination with the play between life and lifeless, animate and inanimate, has strong reverberations with surrealism. Masks, mannequins and paper models were used in his photographs to illuminate the uncanny. They were also employed in his self-portraiture in which he mimicked his idol Charlie Chaplin. These techniques of visual illusion provided a mnemonic tool for the images of his wife in which she is posed and photographed to resemble a doll or mannequin. In the act of art imitating life, ‘Wachspuppenkopf’ is uncanny in its mimicry of the human form with realistic teeth, eyes, skin and even the unusual detail of small wrinkles under the eyes. The downward angle, lighting and odd doubling of the neckline utilizes standard surrealist methods to infer life and movement.

Werner Rohde, Mask, Gelatin Silver Print c. 1920’s

TIM GIDAL (Ignaz Nachum Gidalewitsch) (1909-1996) USA

Self-portrait 1930

Signed: Tim Gidal, self portrait 1930, photograph printed by photographer TG (script in ink on back)

H: 17 7/8” x W: 12 1/16” (framed)

German-born Israeli photojournalist and writer. Gidal studied law, history and art history in Munich and Berlin, and started photography as a Zionist student. His first published pictures appeared in the Münchener illustrierte Presse in 1929. After emigrating in 1933 he lived in Switzerland (where he wrote a doctoral dissertation on photojournalism), the Middle East, and India, contributing to numerous publications. Between 1938 and 1940 he worked for Picture Post, and 1942-5 for the British army magazine Parade. After moving to the USA in 1947 he was an editorial consultant for Life. He later held academic posts in America and Israel. His many books include Modern Photojournalism: Origin and Evolution 1910-1933 (1973).

BARRY L. THUMMA (1947-2003) USA

Face of America 1980

Gelatin silver print

Size: H: 13 3/8” x W: 11”

Size (with board): H: 14” x W: 11”

Size (framed): H: 21 ¼” x W: 17”

Price: $2,750

Barry L. Thumma, a former New Era photographer, covered four presidents as White House photographer for The Associated Press. In his 20-year career with the AP, he traveled on more than 100 Air Force One flights to photograph presidents Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. He also photographed Pope John Paul II, Jerry Falwell, Mikhail Gorbachev, Michael Deaver, Alan Greenspan and Donald Rumsfeld, among other personalities and politicians of his time. He was a member of the White House News Photographers Association. Thumma began his career in 1967 as a part-time photographer for the Lancaster New Era. He joined the Associated Press in 1973 in Cincinnati, where he covered the Reds and the Bengals. After two years as the Ohio photo editor, Thumma moved to Washington, D.C. to cover the White House. He also captured heartbreaking images of the famine in Ethiopia, NASA space flight operations and troop actions in the field.