EUROPEAN JEWELRY

POP & CONTEMPORARY

The bold geometric style of Pop Art flourished in the 60s quickly found its way into jewelry. Diverse materials such as plastics, particularly Plexiglas and vinyl were predominantly used in costume jewelry and colorful stones and enamel were incorporated into silver and precious jewelry. Pop art embraced the highly varied imagery of popular culture. It was in essence anti-functional and ephemeral, reflecting a new code of expendability and shock. Artists like Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselman’s “popular culture” themes come to life and emerge as wearable art forms.

The bold geometric style of Pop Art flourished in the 60s quickly found its way into jewelry. Diverse materials such as plastics, particularly Plexiglas and vinyl were predominantly used in costume jewelry and colorful stones and enamel were incorporated into silver and precious jewelry. Pop art embraced the highly varied imagery of popular culture. It was in essence anti-functional and ephemeral, reflecting a new code of expendability and shock. Artists like Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselman’s “popular culture” themes come to life and emerge as wearable art forms.

View Pop & Contemporary Jewelry here.

POST WAR

After the war jewelry design continued to develop despite the economic difficulties. Forties jewelry is characterized by its chunkiness and the use of contrasting forms and bold designs and often included pleats and drapes simulating fabric. The interest in mechanization is also sometimes reflected in the designs. People still had limited financial resources, so very limited quantities of gold were wrought into designs to create an impression of things being bigger than they really were and thus silver and costume jewelry came into vogue as well.

After the war jewelry design continued to develop despite the economic difficulties. Forties jewelry is characterized by its chunkiness and the use of contrasting forms and bold designs and often included pleats and drapes simulating fabric. The interest in mechanization is also sometimes reflected in the designs. People still had limited financial resources, so very limited quantities of gold were wrought into designs to create an impression of things being bigger than they really were and thus silver and costume jewelry came into vogue as well.

DANISH – SCANDINAVIAN

Though Scandinavia has produced distinctive jewelry at least since the time of the Vikings, the region’s unique industry didn’t come into its own until the late 19th century. Prior to this time, jewelry from the four Scandinavian countries—Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland—drew primarily on early Nordic traditions. Heavily embellished bracelets and pendants featured complex knotted designs showcasing symbolic animals and signs. These pieces emphasized their metal materials, particularly silver, with limited gemstone and pearl decoration. Near the turn of the 20th century, Scandinavian artisans looked to indigenous craft-oriented arts to inform their designs. In Denmark, the Arts and Crafts movement was known as skønvirke, or “beautiful work,” and its jewelry makers relied heavily on a sculptural quality achieved through repoussage or chasing.

Though Scandinavia has produced distinctive jewelry at least since the time of the Vikings, the region’s unique industry didn’t come into its own until the late 19th century. Prior to this time, jewelry from the four Scandinavian countries—Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland—drew primarily on early Nordic traditions. Heavily embellished bracelets and pendants featured complex knotted designs showcasing symbolic animals and signs. These pieces emphasized their metal materials, particularly silver, with limited gemstone and pearl decoration. Near the turn of the 20th century, Scandinavian artisans looked to indigenous craft-oriented arts to inform their designs. In Denmark, the Arts and Crafts movement was known as skønvirke, or “beautiful work,” and its jewelry makers relied heavily on a sculptural quality achieved through repoussage or chasing.

View Danish – Scandinavian Jewelry here.

ART DECO – RAMA – DUTCH

Rama was a both a sculptor and a jewelry maker, who worked alongside the famous and influential artist Joaquin Torres-Garcia. Rama’s atelier, the “Joyas Rama” Julio Herrera y Obes 1330 was located in the famous Montevideo 1920’s Art Deco building, the Palacio Rex. Rama’s jewelry designs were finely crafted and oftenincorporated delicate open work and stone setting amidst repeat geometric patterns and bold machine-age forms.

Rama was a both a sculptor and a jewelry maker, who worked alongside the famous and influential artist Joaquin Torres-Garcia. Rama’s atelier, the “Joyas Rama” Julio Herrera y Obes 1330 was located in the famous Montevideo 1920’s Art Deco building, the Palacio Rex. Rama’s jewelry designs were finely crafted and oftenincorporated delicate open work and stone setting amidst repeat geometric patterns and bold machine-age forms.

Dutch Jewelry, also known as “Amsterdam School” was crafted in hammered copper or silver and often mounted with cabochons of the quartz family, (agate, chrysocolla, chrysoprase or carnelian) and sometimes set in cloisonné enamel. The Amsterdam School’s foreign influence was neither Celtic nor Japanese, but Indonesian, where the Muslim artists of the Dutch East India colonies created their decorative arts with geometric abstractions. The Arts & Crafts movement was fuelled by a reverence for traditional handicrafts and environmental concerns, protecting the countryside from advancing industrialization. Returning to nature was celebrated In England with floral designs, but in the Dutch lowlands, organic shapes were taken from the sea, revolving around the endlessly inventive shapes of the shell. These were often adorned with coral cabochons and were hand-hammered to illustrate the handcrafted technique.

View Art Deco-RAMA-Dutch Jewelry here.

FRENCH ART NOUVEAU

Art Nouveau jewelry, popular from the mid-1890s until about 1910 is characterized by soft, curved shapes and lines, and usually features natural designs such as flowers, birds, and animals. The female body is a popular theme and is featured on a variety of jewelry pieces, especially cameos. A close cousin of Arts and Crafts jewelry, whose motifs tend to be stylized and controlled, Art Nouveau jewelry favors stones such as agate, garnet, and opal, and techniques like enameling. Long necklaces made of pearls were common, as were sterling-silver chains punctuated by glass beads or ending in a silver or gold pendant, itself often designed as an ornament to hold a single, faceted jewel of amethyst, peridot, or citrine and sometimes featuring colorful enamels or plique-a-jour. Plique-à-jour is French for “for daylight to shine through,” plique-à-jour enamel is translucent, meaning it allows light to pass through similar to a stained glass window.

Art Nouveau jewelry, popular from the mid-1890s until about 1910 is characterized by soft, curved shapes and lines, and usually features natural designs such as flowers, birds, and animals. The female body is a popular theme and is featured on a variety of jewelry pieces, especially cameos. A close cousin of Arts and Crafts jewelry, whose motifs tend to be stylized and controlled, Art Nouveau jewelry favors stones such as agate, garnet, and opal, and techniques like enameling. Long necklaces made of pearls were common, as were sterling-silver chains punctuated by glass beads or ending in a silver or gold pendant, itself often designed as an ornament to hold a single, faceted jewel of amethyst, peridot, or citrine and sometimes featuring colorful enamels or plique-a-jour. Plique-à-jour is French for “for daylight to shine through,” plique-à-jour enamel is translucent, meaning it allows light to pass through similar to a stained glass window.

View French Art Nouveau Jewelry here.

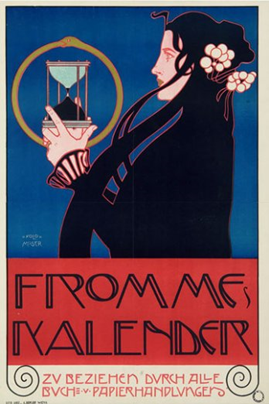

AUSTRIAN ART NOUVEAU

Stylistic trends in Vienna took a significantly different direction. Led by Austrian artist Gustav Klimt, young artists and architects formed a group called the Wiener Sezession, or Vienna Secession, in protest against the entrenched conservatism of the art establishment in Vienna. As did their counterparts elsewhere in Europe, Secession designers rejected historical styles; but in Vienna they began expressing their design ideas through an increasing simplification of form. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was also an influential figure in Vienna at that time with having exhibited his unique and fluid designs at the 1900 Secession Exhibition. The elegance of Art Nouveau carried through into the first couple years of the 20th Century, but soon gave way to the paired down and geometric simplicity of the Wiener Werkstaette.

Stylistic trends in Vienna took a significantly different direction. Led by Austrian artist Gustav Klimt, young artists and architects formed a group called the Wiener Sezession, or Vienna Secession, in protest against the entrenched conservatism of the art establishment in Vienna. As did their counterparts elsewhere in Europe, Secession designers rejected historical styles; but in Vienna they began expressing their design ideas through an increasing simplification of form. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was also an influential figure in Vienna at that time with having exhibited his unique and fluid designs at the 1900 Secession Exhibition. The elegance of Art Nouveau carried through into the first couple years of the 20th Century, but soon gave way to the paired down and geometric simplicity of the Wiener Werkstaette.

View Austrian Art Nouveau Jewelry here.

GERMAN MODERN BAUHAUS

The focus of the Bauhaus movement was on architectural and industrial design in all mediums. Its credo was “dedication to the unity of the arts with the crafts.” Though it was only in existence from 1919 to 1933, the Bauhaus School, started by Walter Gropius, had a huge impact on the art world. It had among its extraordinary staff members such luminaries in the contemporary art and design world as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Mies van der Rohe. Many of these influential artists left Germany when the school closed its doors in 1933 and sought asylum in other European countries and particularly in the United States, where they spread their credo of “less is more.” Through this credo, they were setting the stage for a century of clean-lined, geometric, contemporary design and art, which also was inherent to Modernist German jewelry.

The focus of the Bauhaus movement was on architectural and industrial design in all mediums. Its credo was “dedication to the unity of the arts with the crafts.” Though it was only in existence from 1919 to 1933, the Bauhaus School, started by Walter Gropius, had a huge impact on the art world. It had among its extraordinary staff members such luminaries in the contemporary art and design world as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Mies van der Rohe. Many of these influential artists left Germany when the school closed its doors in 1933 and sought asylum in other European countries and particularly in the United States, where they spread their credo of “less is more.” Through this credo, they were setting the stage for a century of clean-lined, geometric, contemporary design and art, which also was inherent to Modernist German jewelry.

View German Modern Bauhaus Jewelry here.

GERMAN JUGENDSTIL

German Art Nouveau is commonly known by its German name, Jugendstil. The name is taken from the artistic journal, Die Jugend, which was published in Munich and which espoused the new artistic movement. It was founded in 1896 by Georg Hirth. The magazine was instrumental in promoting the style in Germany and as a result, its name was adopted as the most common German-language term for the style: Jugendstil. Jugendstil jewelry in Germany generally took its themes from nature. Flowers, along with other plants, were particularly well represented. The principle designers’ works were prolifically copied in lesser materials such as alpaca, copper and glass but with excellent workmanship to create jewelry for the middle class. Theodor Fahrner (1868-1929) was a major producer of jewelry in this style. Drawing on the Darmstadt colony of artisans, Farhner made jewelry with avant-garde designs of the period. The two main centers for Jugendstil art in Germany were Munich and Darmstadt.

German Art Nouveau is commonly known by its German name, Jugendstil. The name is taken from the artistic journal, Die Jugend, which was published in Munich and which espoused the new artistic movement. It was founded in 1896 by Georg Hirth. The magazine was instrumental in promoting the style in Germany and as a result, its name was adopted as the most common German-language term for the style: Jugendstil. Jugendstil jewelry in Germany generally took its themes from nature. Flowers, along with other plants, were particularly well represented. The principle designers’ works were prolifically copied in lesser materials such as alpaca, copper and glass but with excellent workmanship to create jewelry for the middle class. Theodor Fahrner (1868-1929) was a major producer of jewelry in this style. Drawing on the Darmstadt colony of artisans, Farhner made jewelry with avant-garde designs of the period. The two main centers for Jugendstil art in Germany were Munich and Darmstadt.

View German Jugendstil Jewelry here.

WIENER WERKSTÄTTE

The Wiener Werkstätte created jewelry under the design supervision of Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956). Established in 1903, the Wiener Werkstätte was a production community of visual artists in Vienna, Austria bringing together architects, artists and designers. The enterprise evolved from the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 as a progressive alliance of artists and designers. From the start, the Secession had placed special emphasis on the applied arts, and its 1900 exhibition surveying the work of contemporary European design workshops prompted the young architect Josef Hoffmann and his artist friend Koloman Moser to consider establishing a similar enterprise. The Wiener Werkstätte emphasized the interaction between designer and those executing the design, thus insuring the continuity of the design. The beauty of Wiener Werkstätte jewelry — the first products made after the workshops began, in 1903 — lies in the way it blurs the line between precious ornament and miniature sculpture. Seeing jewelry as art was central to the Wiener Werkstätte philosophy. Its ideal was the “gesamtkunstwerk”, or total work of art, in which all elements of art, design and craft cohered into a visually unified entity. The value of Wiener Werkstätte jewelry came not from the raw materials but from its aesthetic, the purview of artists and designers, and its craftsmanship, handled by the workshop’s expert artisans.

The Wiener Werkstätte created jewelry under the design supervision of Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956). Established in 1903, the Wiener Werkstätte was a production community of visual artists in Vienna, Austria bringing together architects, artists and designers. The enterprise evolved from the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 as a progressive alliance of artists and designers. From the start, the Secession had placed special emphasis on the applied arts, and its 1900 exhibition surveying the work of contemporary European design workshops prompted the young architect Josef Hoffmann and his artist friend Koloman Moser to consider establishing a similar enterprise. The Wiener Werkstätte emphasized the interaction between designer and those executing the design, thus insuring the continuity of the design. The beauty of Wiener Werkstätte jewelry — the first products made after the workshops began, in 1903 — lies in the way it blurs the line between precious ornament and miniature sculpture. Seeing jewelry as art was central to the Wiener Werkstätte philosophy. Its ideal was the “gesamtkunstwerk”, or total work of art, in which all elements of art, design and craft cohered into a visually unified entity. The value of Wiener Werkstätte jewelry came not from the raw materials but from its aesthetic, the purview of artists and designers, and its craftsmanship, handled by the workshop’s expert artisans.

View Wiener Werkstätte Jewelry here.

19th CENTURY BRITISH

Art Nouveau in Britain evolved out of the already established arts and crafts movement. Founded in 1861 by English designer William Morris, the arts and crafts movement emphasized the importance of handcrafted work. Morris’s devotion to handmade articles was a reaction against shoddy machine-made products that were flooding the English marketplace as the industrial revolution expanded. The arts and crafts movement also promoted a totally designed environment in which everything from wallpaper to silverware is made according to a unified design. British art nouveau designers of the 1890s shared Morris’s dedication to handcrafted work and integrated designs. To these principles they added new forms and materials, establishing the aesthetic of the art nouveau style.

Art Nouveau in Britain evolved out of the already established arts and crafts movement. Founded in 1861 by English designer William Morris, the arts and crafts movement emphasized the importance of handcrafted work. Morris’s devotion to handmade articles was a reaction against shoddy machine-made products that were flooding the English marketplace as the industrial revolution expanded. The arts and crafts movement also promoted a totally designed environment in which everything from wallpaper to silverware is made according to a unified design. British art nouveau designers of the 1890s shared Morris’s dedication to handcrafted work and integrated designs. To these principles they added new forms and materials, establishing the aesthetic of the art nouveau style.

View 19th Century British Jewelry here.

ARTS & CRAFTS

The graphic, stylized aesthetic of Arts and Crafts lends itself beautifully to jewelry. Simple motifs such as flower petals and leaves are perfect design elements, they can double as naturalistic shapes that are appealing in their own right, as well as armatures for decoration, whether filled in with enamel or hammered to create surface patterns. In England, the self-taught silversmith C. R. Ashbee, who established the Guild of Handicraft in 1888, used only a handful of elements to create his famous butterfly brooch, which was also available as a necklace. In this rendition the insect’s blue enamel wings were complemented by dangling turquoise stones set within silver bands and suspended from silver chains. Ashbee inspired a generation of English Arts and Crafts jewelers, including Archibald Knox, who did some of his best work for the department store Liberty & Co., whose succeeded in greatly popularizing the Arts and Crafts movement.

The graphic, stylized aesthetic of Arts and Crafts lends itself beautifully to jewelry. Simple motifs such as flower petals and leaves are perfect design elements, they can double as naturalistic shapes that are appealing in their own right, as well as armatures for decoration, whether filled in with enamel or hammered to create surface patterns. In England, the self-taught silversmith C. R. Ashbee, who established the Guild of Handicraft in 1888, used only a handful of elements to create his famous butterfly brooch, which was also available as a necklace. In this rendition the insect’s blue enamel wings were complemented by dangling turquoise stones set within silver bands and suspended from silver chains. Ashbee inspired a generation of English Arts and Crafts jewelers, including Archibald Knox, who did some of his best work for the department store Liberty & Co., whose succeeded in greatly popularizing the Arts and Crafts movement.

View Arts & Crafts Jewelry here.

RUSSIAN-NORWEGIAN

Norway distinguished itself in the enameled metal arts, and firms like J. Tostrup, Marius Hammer, and David-Andersen adapted the basse-taille and plique-à-jour techniques for jewelry production. Most of these enameled pieces reflected the reigning Art Nouveau trends of bright colors and densely layered floral shapes.

Norway distinguished itself in the enameled metal arts, and firms like J. Tostrup, Marius Hammer, and David-Andersen adapted the basse-taille and plique-à-jour techniques for jewelry production. Most of these enameled pieces reflected the reigning Art Nouveau trends of bright colors and densely layered floral shapes.

Likewise in Russia, enamels were featured as well as Niello. Niello is a black alloy of copper, silver, and lead sulphides, used as an inlay on engraved or etched metal. The Egyptians are credited with originating niello decoration, which spread throughout Europe during the late Iron Age and is common in Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and other types of Early Medieval jewelry.