Gouache

-

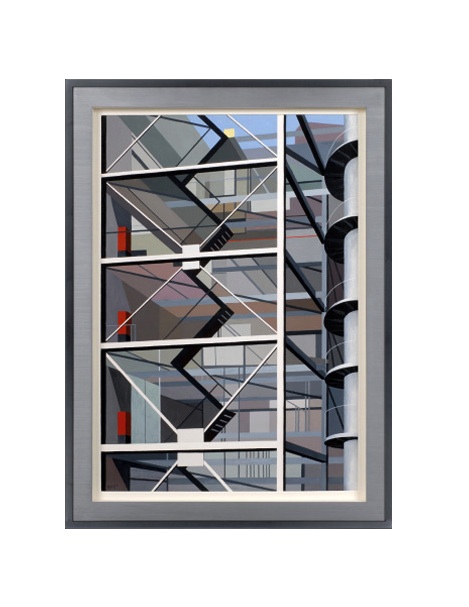

Richard Harold Redvers Taylor, “Modernist building staircase”, Gouache on paper c. 1949

RICHARD HAROLD REDVERS TAYLOR (1900-1975) United Kingdom

Modernist building staircase c. 1949

Gouache on paper, metal and wood frame

Signed: RHRT (lower left)

Marks: Gimpel Fils exhibition label (on back)

Exhibited: “An Exhibition in the Kettle’s Yard Loan Gallery: Sculpture & Painter,

14 February – 10 March, 1972” Gimpel Fils, London

Framed: H: 41 7/16” x W: 30 5/16”

Richard Harold Redvers Taylor (1900-1975) was born in Brighton on March 14th, 1900 and educated at Brighton College and Heatherleys School of Fine Art, Chelsea. His father, Harold Taylor, was a headmaster. Redvers Taylor retired from the Army (where he specialized in topographical surveying in Africa) in 1937 but was recalled for war service. In 1946 he began a new career as a professional painter. Between 1948 and 1958 Taylor was given a series of six one-man shows by Lefevre and Gimple Fils in London. In the 1960’s he turned to sculpture, and in 1972 an exhibition of his sculpture and paintings was held at the Kettle’s Yard Loan Gallery in Cambridge. His work is held in the permanent collection at the Beith Uri V Rami Museum in Israel. Louise Taylor (née Hayden), his wife, was an American and the adopted daughter and heiress of Alice B. Toklas, the companion of Gertrude Stein. Louise Taylor died on 21 July 1977.

Purism, otherwise known as l’esprit nouveau was directly inspired by a spare, functionalist aesthetic and is closely associated with the work of Le Corbusier and his circle in Paris in the second quarter of the 20th Century. In America this purist style was known as Precisionism, which explored similar imaginary during the late 1920’s and 30’s with artists like Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth and Ralston Crawford at the forefront of this movement. In England, the Vorticist movement (1912-1915) was founded by Wyndham Lewis and others and was the precursor to the Purist movement in Great Britain in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Redvers Taylor created geometrical landscapes while reducing volumes to colored planes and outlines to ridges. His artwork combines depth and perspective with flattened cubist fields of color. Architecture of industrial buildings was his favorite subject, whereas people and nature were usually absent from his compositions.

-

Charles Martin, “Bal Masque”, Pencil, ink, gouache and watercolor on paper 1927

CHARLES MARTIN (1884-1934) France

Bal Masque 1927

Pencil, ink, gouache and watercolor on paper.

Signed: Martin (lower right corner); A l’Ami Koval, l’Ami Martin, Bien Amicalement (upper left corner)

H: 8” x W: 11 7/16”

Price: $12,500

Charles Martin was a notable French illustrator, graphic artist, posterist, fashion and costume designer. His drawings are charming, amusing and sophisticated. The artist studied at the Montpelier Ecole des Beaux Arts, Academie Julian and Ecole Des Beaux Arts, Paris. Throughout his career, Martin was also a contributor to the French fashion journals Gazette du Bon Ton, Modes et Manieres d’Aujourd’hui, Journal Des Dames et Des Modes, and Vogue. His illustrated books include the hat catalogue “Les Modes en 1912,” the erotic “Mascarades et Amusettes” 1920, and “Sports et Divertissements” 1919, written in collaboration with composer Erik Satie.

-

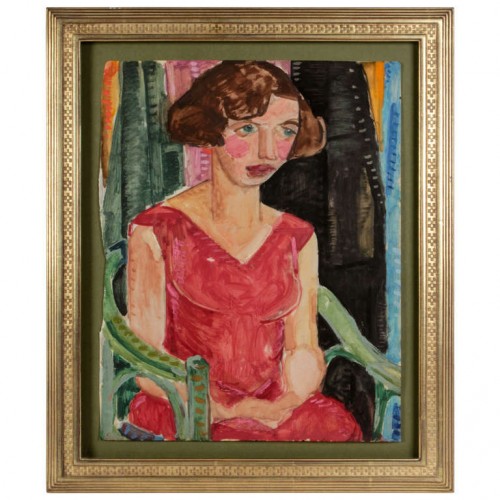

Isobel Steele MacKinnon, Weimar Portrait, Gouache, tempera and oil on paper c.1927

ISOBEL STEELE MACKINNON (1896 – 1972) USA

Weimar Portrait c.1927

Gouache, tempera and oil on paper, lemon gold frame.

Signed: MacKinnon

Exhibited: Weimar Portraits, Riviera Landscapes: A Chicagoan in Hofmann’s Studio, 1925–1929, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL, March 28 – May 3, 2008

Illustrated: Weimar Portraits, Riviera Landscapes: A Chicagoan in Hofmann’s Studio, 1925–1929, exhibition catalog, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL, March 28 – May 3, 2008

Painting: H: 16 1/2″ x W: 13″

Frame: H: 20 1/2″ x W: 17 1/4″SOLD

***This colorful and mesmerizing painting rather closely foreshadows the famous portraiture of the renowned American artist Alice Neel (1900-1984). Isobel Steele MacKinnon’s adventures as an American artist living and working in Europe echo those of many other expatriates of the epoch. MacKinnon and her husband Edgar Rupprecht were, by the time they left Chicago in 1925, both established figures in Chicago’s art world, and especially in Saugatuck, Michigan, where they taught at Ox-Bow Summer School. What the couple encountered in the studio of German artist Hans Hofmann would rock the impressionist foundations of their artwork and transform them into committed modernists. Hofmann’s Munich-based school was a magnet for foreign students after World War I, ever after Hofmann left Germany in the early Thirties. Indeed, over the period of four years (1925 to 1929) during which Steele and Rupprecht worked alongside Hofmann, their fellow students included renowned abstract artist Vaclav Vytlacil and painter Worth Ryder, the artist who would invite Hofmann to teach in the US for the first time in 1930. A small, elegant, realistic profile drawing Rupprecht made of MacKinnon in 1925 makes fascinating contrast with the work she produced while in Europe. In Chicago, her approach had been as conventional as his, but under Hofmann she took to the new ideas with startling ease, absorbing his “push and pull” spatial concept and his deep investigations of the compositional consequences of hot and cold colors. The portraits of German and other expat sitters made at the time have the analytic angularity associated with Hofmann, drawn and painted with a palpable power and sureness. Some resemble expressionists like Oskar Kokoschka or Ludwig Meidner. For instance, the small portrait of a rat-like man with a whiskery mustache or the jutting, harsh jaw of a stern woman with a fur collar, and a rosy-cheeked girl in red (this painting), straight from a German cabaret. More radical than her portraits, MacKinnon’s slashing charcoal gesture drawings of figures are sometimes exceptionally abstract, hauntingly presaging the abstract expressionist women of Willem de Kooning. These works represent an artist in the throes of letting herself loose, shaking off the constrictions of academicism, experimenting with vital energy and displaying an unwavering hand. During their European summers, MacKinnon and Rupprecht traveled with Hofmann. MacKinnon had quickly risen to become his premier student. On Capri and St. Tropez, she painted bright, abstracted landscapes, often based on carefully plotted line drawings. The warm environs often drew out her old impressionist tendencies, but in the most advanced of these works she blocked colors into shapes and patterns that suggest Marsden Hartley, Milton Avery or, in some cases, Jan Matulka. In one drawing, probably from Paris, she has sculpted the trees into architectural forms. After their sojourn, which extended from their studies with Hofmann to several years as active artists in Paris, MacKinnon and Rupprecht returned to Chicago. They were rejuvenated, heads full of new ideas, portfolios brimming with the work they’d done. When WWII was over, Steele began a long and fruitful teaching career at the School of the Art Institute. From this post she introduced many young artists, from Jack Beal to Tom Palazzolo, to Hofmann’s concepts at the same time he was teaching the future abstract expressionists of America from his schools in New York and Provincetown. In recognition of her unwavering interest in issue of space in pictoral composition, MacKinnon’s closest students were known as the “space cadets.” A larger-than-life character, she died in Chicago in 1972 after a protracted battle with Alzheimer’s.