Self-portrait

-

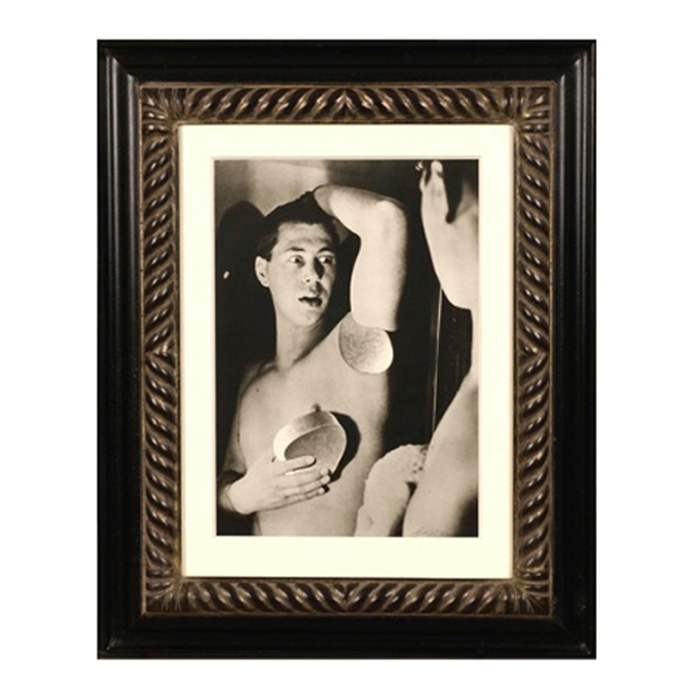

Herbert Bayer, Self Portrait, Gelatin silver print , 1932, printed later

HERBERT BAYER (1900-1985) Austria

Self portrait 1932 (printed later)

Silver gelatin print

Edition: 28/40

Signed: bayer 32 (in ink on bottom right corner)

Provenance: Kennedy Gallery, New York

H: 13 7/16” x W: 9 ½”

Framed size: H: 21 ½” x W: 17 ½”

Price: $16,000

Herbert Bayer (1900 – 1985) was an Austrian graphic designer, painter, photographer, and architect. Bayer apprenticed under the artist Georg Schmidthammer in Linz. Leaving the workshop to study at the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony, he became interested in Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus manifesto. After Bayer had studied for four years at the Bauhaus under such teachers as Wassily Kandinsky and László Moholy-Nagy, Gropius appointed Bayer director of printing and advertising. In the spirit of reductive minimalism, Bayer developed a crisp visual style and adopted use of all-lowercase, sans serif typefaces for most Bauhaus publications. Bayer is one of several typographers of the period including Kurt Schwitters and Jan Tschichold who experimented with the creation of a simplified more phonetic-based alphabet. Bayer designed the 1925 geometric sans-serif typeface, universal, now issued in digital form as Architype Bayer that bears comparison with the stylistically related typeface Architype Schwitters.

In 1928, Bayer left the Bauhaus to become art director of Vogue magazine’s Berlin office. He remained in Germany far later than most other progressives. In 1936 he designed a brochure for the Deutschland Ausstellung, an exhibition for tourists in Berlin during the 1936 Olympic Games. In 1938 he left Germany and settled in New York City where he had a long and distinguished career in nearly every aspect of the graphic arts. In 1946 Bayer relocated again. Hired by industrialist and visionary Walter Paepcke, Bayer moved to Aspen, Colorado as Paepcke promoted skiing as a popular sport. Bayer’s architectural work in the town included co-designing the Aspen Institute and restoring the Wheeler Opera House, but his production of promotional posters identified skiing with wit, excitement, and glamour. Bayer would remain associated with Aspen until the mid-1970s. Bayer gave the Denver Art Museum a collection of around 8,000 of his works. In 1959, he designed his “fonetik alfabet”, a phonetic alphabet, for English. It was sans-serif and without capital letters. He had special symbols for the endings -ed, -ory, -ing, and -ion, as well as the digraphs “ch”, “sh”, and “ng”. An underline indicated the doubling of a consonant in traditional orthography.

-

Werner Rohde, Self-portrait, Silver gelatin print 1926

WERNER ROHDE (1906-1990) Germany

Self-portrait 1926

Silver gelatin print, ebonized wood frame

Signed: Werner Rohde 1926 (pencil signature and date on back on photo); inv. 3RMG 1081.27

Photo: H: 6 13/16” x W: 4 15/16”

Framed: H: 16 5/16” x W: 14 3/8”Price: $38,000

Werner Rohde’s visual play with the animate and inanimate draws him close to the aesthetics of the surrealists while maintaining a strong alignment with Germany’s new-vision avant-garde. Rohde experimented widely with double exposures, photomontage, perspective and dramatic lighting that reflected his interest in filmic effects. The son of a glass painter (a medium he would turn to later in life), Rohde took up photography during his studies at the Arts and Craft School in Halle. Like Kesting, Willy Zielke and Kretschmer, he participated in the 1929 ‘Film und foto’ exhibition in Stuttgart that remains one of the historical focal points for Germany’s new photographic vision. Despite this early recognition of his work, Rohde fell into obscurity after the war until the rediscovery of his photographs in the mid 1970s.

Rohde’s fascination with the play between life and lifeless, animate and inanimate, has strong reverberations with surrealism. Masks, mannequins and paper models were used in his photographs to illuminate the uncanny. They were also employed in his self-portraiture in which he mimicked his idol Charlie Chaplin. These techniques of visual illusion provided a mnemonic tool for the images of his wife in which she is posed and photographed to resemble a doll or mannequin. In the act of art imitating life, ‘Wachspuppenkopf’ is uncanny in its mimicry of the human form with realistic teeth, eyes, skin and even the unusual detail of small wrinkles under the eyes. The downward angle, lighting and odd doubling of the neckline utilizes standard surrealist methods to infer life and movement.