Product Description

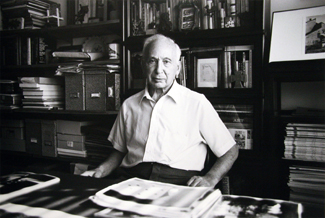

Andre Kertesz, Paris, Silver gelatin print 1927

ANDRÈ KÈRTESZ (1894-1985) Hungary

Paris 1927

Silver gelatin print

Signed: Paris 1927, A.Kertesz, Page 150 (in pencil on back); ANDRÈ KÈRTESZ (stamped on back).

Framed size: H: 16 5/8” x W: 17 13/16”

Throughout most of his career, Kertész was depicted as the “unknown soldier” who worked behind the scenes of photography, yet was rarely cited for his work, even into his death in the 1980s. His work itself is often described as predominantly utilizing light and even Kertész himself said that “I write with light”. He was never considered to “comment” on his subjects, but rather capture them – this is often cited as why his work is often overlooked; he stuck to no political agenda and offered no deeper thought to his photographs other than the simplicity of life. With his art’s intimate feeling and nostalgic tone, Kertész’s images alluded to a sense of timelessness that was inevitably only recognized after his death. Unlike other photographers, Kertész’s work gave an insight into his life, showing a chronological order of where he spent his time; for example, many of his French photographs were from cafés where he spent the majority of his time waiting for artistic inspiration. Although Kertész rarely received bad reviews, it was the lack of them that lead to the photographer feeling distant from recognition. Now however, he is often considered to be the father of photojournalism. Even other photographs cite Kertész and his photographs as being inspirational; Henri Cartier-Bresson once said of him in the early 1930s, “We all owe him a great deal”.

Andre Kertesz, Paris, Silver gelatin print 1927

PAUL HAUSTEIN (1880-1944) Germany

HERMANN BEHRND (b. 1849) SILBERWARENFABRIK (silver) Dresden, Germany

JAKAB RAPOPORT (enamelist) Budapest, Hungary

Inkwell c. 1900

Multicolored burgundy, purple, blue and green enamel with silver mounts, glass insert

Marks: Moon, crown, 800, HB (Hermann Behrnd mark)

Same model with variant mount illustrated: Deutsche Goldschmiede-Zeitung, n.d. (circa 1903-05), p. 23

For related works and more information see: Art Nouveau in Munich: Masters of Jugendstil, ed. Kathryn Bloom Hiesinger (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1988) pp. 67-69; Jugendstil in Dresden, Aufbruch in die Moderne, Gisela Haase et al., exh. cat. (Dresden: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden; Wolfratshausen: Edition Minerva, 1999).

Dia: 7 1/4″ x H: 4 1/2″

Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution with compelling evidence in his 1859 book “On the Origin of Species” overcoming scientific rejection of earlier concepts of transmutation of specie. By the 1870s both the scientific community and much of the general public had accepted evolution as a fact and awakening the public to the diversity of life. The frog emerging from Darwin’s Pond was a symbol of the times and a favorite theme for jewelry of the era.

NATHAN LERNER (1913-1997) Chicago, USA

Dowels Light Box Study c.1937

Silver gelatin print

Signed on back

Illustrated: New Bauhaus, 50 Jahre: Bauhausnachfolge in Chicago (Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv and Argon Verlag GmbH: 1987), p. 177

H: 18 5/8” x 22 ½” (framed)

Nathan Lerner’s long career was inextricably bound up in the history of visual culture in Chicago. Born in 1913 to immigrants from Ukraine, he began studying painting at the Art Institute of Chicago at the age of 16, taking up the camera to perfect his compositional skills. At 22 he began doing a kind of photojournalism, developing his well-known series on ”Maxwell Street,” an immigrant neighborhood hit hard by the Depression, and also photographing the southern Illinois mining area. In 1936 when the New Bauhaus was established in Chicago by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, Lerner became one of its first scholarship students and turned increasingly to photographic experimentation. He began making semi-abstract, strongly Constructivist images involving luminous projections, solarization, photograms and other methods, and his interest in manipulating light led him to invent the first ”light box.” In 1939 he became the assistant of Gyorgy Kepes, head of the school’s light workshop; together, they wrote ”The Creative Use of Light” (1941). With Charles Niedringhaus in 1942 he developed a machine for forming plywood that was used in making most of the school’s furniture. After working as a civilian light expert for the Navy in New York during World War II, Lerner returned to the school, now called the Institute of Design, and was named education director after Moholy-Nagy’s death in 1946. He left in 1949, opening a design office that became nationally known for its furniture, building systems and glass and plastic containers (including bottles for Revlon and Neutrogena and the Honeybear honey container). In 1968 Lerner married Kiyoko Asia, a classical pianist from Japan, and over the next two decades made numerous trips to Japan, where he took his first color photographs, as well as Mexico. He had his first solo exhibition of photography in 1973 and thereafter exhibited regularly in galleries and museums in the United States, Europe and Japan. His work is included in photography and design collections around the world. (Roberta Smith, New York Times, February 15, 1997).