Product Description

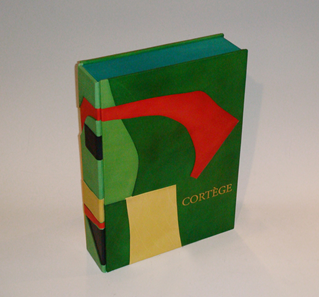

Andre Lanskoy, Maurice Beaufume, Pierre Lecuire, “Cortege” 1959

ANDRE LANSKOY (1902-1976) France

MAURICE BEAUFUME

PIERRE LECUIRE

“Cortege” 1959

64pp, 25 illustrations by Andre Lanskoy and Maurice Beaufume

Cortège is now often compared to “Jazz” as perhaps the finest example of

pochoir in the postwar period. Printed on Arches Vellum paper.

Dimensions:

Book: H: 18” x W: 13 3/8” x D: 1 7/8”

Custom leather box 2008: H: 20 ¼” x W: 15” x D: 4 ½”

Custom silk slipcase: H: 21 ½” x W: 15 5/8” x D: 5 3/8”

The artworks of André Lanskoy (1902-1976) are more than abstractions—they are juxtapositions of shapes, assemblages of colors and studies that explore the interfacing of language with visual imagery. A pioneer of Tachism, an artistic movement of the 1940s and 1950s also known as Art Informel or Lyrical Abstraction, Lanskoy emphasized the spontaneous in his paintings, combining surges of pure color with more subtle modulations. His efforts to translate language into abstract visual messages are most evident in two of his bold projects: a rare screen-printed textile and his vivid collages for Pierre Lecuire’s book, Cortège.

Born in Moscow, Lanskoy spent his youth in Russia; in 1921, he moved to Paris and studied at the Académie de la Grande-Chaumière. His first non-figurative works were painted in 1937, with his first Parisian exhibition of abstractions in 1944. As a painter, Lanskoy gave primacy to color, and this holds true for his textile design, Egypte. In 1946, French industrialist Jean Bauret invited several Tachist artists—including Serge Poliakoff, André Beaudin and Henri Michaux—to experiment with designs for furnishing textiles. One of Lanskoy’s contributions to this series was an expressive interpretation of the complex pictorial characters of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. The relationship between the Egyptian writing system and his own glyphs is mainly conceptual: the symbols Lanskoy invented have no inherent meaning, yet their careful placement suggests a text that is meant to be read. Contrasting with the neutral ground, the centered, vertical column is a grid of rectangular cells containing six repeating compilations of mysterious, hieroglyphic-inspired shapes. These cartouche-like compartments are bordered on each side by narrow strips of color blocks with voided linear abstractions. The intense purple and teal hues and vibrant reds and yellow are typical of Lanskoy’s exaltation of color.

Working within the theme of synthesizing language, color and form, Lanskoy tried his hand at an exciting tradition: the livre d’artiste. His first project was a collaboration with poet Pierre Lecuire; their masterpiece Cortège, arguably one of the finest artist-books ever produced, is a dazzling symbiosis of literary and visual material. Lecuire first met Lanskoy in 1948; ten years later, he would enlist his friend to illustrate the long prose poem. At Lecuire’s suggestion, Lanskoy created a series of twenty-four compositions for the book in the papiers collés method; his challenge was to interpret Lecuire’s writing into bold, graphic statements. The author’s opening lines set the tone for Lanskoy’s luminous color harmonies: “This book is a cortège. It has its colors, action and animation. It blazes, it proclaims one knows not which passion, which justice; it flows like the course of a navigation….” As he achieved with Egypte, the vibrant, saturated tints of the abstractions on these particular plates create a language of their own, while the lively arrangement of crisp and jagged forms shows an affinity with the rhythmic cadence of communication.

Remarkable for their dense bursts of color and unfamiliar shapes, the series of collages was masterfully executed in pochoir by colorist Maurice Beaufumé under Lanskoy’s personal direction. The bold, oversized text was printed by Marthe Fequet and Pierre Baudier, and Cortège was released in Paris, December 1959

Andre Lanskoy, Maurice Beaufume, Pierre Lecuire, “Cortege” 1959

ARCHIBALD KNOX (1864-1933) UK

LIBERTY & CO. London

Extremely rare and important grand clock by Archibald Knox for Liberty & Co. This is the largest of all of the Tudric models designed and is inset with abalone shell on the sides, the front corners and on the hands of the clock.

Marks: TUDRIC, 098

Illustrated: The Designs of Archibald Knox for Liberty & Co., A..J. Tilbrook (London: Ornament Press Ltd., 1976) pg. 88; The Liberty Style, (Japan: Hida Takayama Museum of Arts, 1999) fig. 168, p 114; Archibald Knox, ed. by Stephen A. Martin (London: Academy Editions, 1995) p. 88.

H: 15″ x W: 7″ x D: 5″

***This is the largest clock designed by Archibald Knox for

Liberty & Co. and one of only three models known.

MARCEL WANDERS (1963-) The Netherlands

“One morning they woke up” mosaic occasional table or stool 2004

Gilt and lively colored glass mosaic, fiberglass body

H: 13″ x D: 17″

Price: $18,500

Marcel Wanders (1963) grew up in Boxtel, the Netherlands, and graduated at the School of the Arts Arnhem in 1988 with a cum laude certificate. He is now an independent industrial product designer operating out of Amsterdam where he has his own studio, Marcel Wanders studio. Marcel continues to work on diverse products and projects for Cappellini, Mandarina Duck, Magis, Droog Design and Moooi amongst others. For the latter he is associated as creative director. Marcel also co-operates in other design-related projects, such as the Vitra Summer Workshop where he was project leader for the second time. Also he was a juror for various prizes like the Rotterdam Design Prize (for which his own products were nominated several times) and the Kho Liang Ie prize. He lectured at SFMoMA, Limn the Design Academy and has taught at various design academies in the Netherlands. Marcel won the Rotterdam Design Prize (public prize) for the Knotted Chair, and received several other awards including the George Nelson Award (Interiors magazine) and Alterpoint Design Award 2000. In the 2001, Marcel has been nominated in the category ‘designer of the year’ in WIRED magazine’s 2001 wired rave awards. Designs of Marcel Wanders have been selected for the most important design collections and exhibitions in the world, like the Museum of Modern Art in New York and San Francisco, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Central Museum in Utrecht, and various Droog Design exhibitions. In the book ‘Wanders Wonders, design for a new age’ (1999) which accompanied a solo exhibition in Museum ‘t Kruithuis in Den Bosch, the most important products are shown, from the Knotted Chair to the Shadows lamps and from the Nomad Carpet to the Eggvase. Works of Marcel have been published in all leading design magazines.

HENRI MATISSE (1869-1954) France

“Verve” Vol. IX No. 35 & 36 1958

Revue artistique et littéraire paraissant quatre fois par an

Created and editioned at the Mourlot Studio, Paris.

Published by E. Tériade, Paris 1958.

Dimensions:

Book: H 14 1/2” x W: 10 11/16”

Custom leather box: H: 15 13/16” x W: 11 5/8” x D: 2 1/16”

Custom linen case: H: 16 3/4” x 12 5/16” x D: 2 5/8”

Sori Yanagi (1915-2012), Japan

Tendo Co. Ltd., Japan

Butterfly stool, 1956.

Bleached rosewood veneer on plywood with brass.

H: 15” x W: 16 ½” x D: 12”

Price: $4,900

This model can be found in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

The Japanese designer Sori Yanagi is best known for his 1956 Butterfly Stool. It is both elegant and utterly simple: two curved pieces of molded plywood are held together through compression and tension by a single brass rod. The stool’s graceful shape recalls a butterfly’s wings, and has also been compared to the form of torii, the traditional Shinto shrine gates. He loved traditional Japanese crafts and was dedicated to the modernist principles of simplicity, practicality and tactility that are associated with Alvar Aalto, Charles and Ray Eames, and Le Corbusier.”

Yanagi, who studied architecture and art at Tokyo’s Academy of Fine Art, was inspired by the work of Le Corbusier and by the designer Charlotte Perriand, with whom he worked in the early 1940s, while she was in Tokyo as the arts and crafts adviser to the Japanese Board of Trade. But perhaps the most indelible influence on Yanagi was that of his father, Soetsu Yanagi, who led the “mingei” movement, which celebrated Japanese folk craft and the beauty of everyday objects, and who founded the Nihon Mingeikan (or Japanese Folk Crafts Museum) in Tokyo. Yanagi fils, who was named director of the museum in 1977, succinctly described his design aesthetic in a 2002 interview in The Japan Times: “I try to create things that we human beings feel are useful in our daily lives. During the process, beauty is born naturally.” Throughout his life, Sori Yanagi was inspired by what he called “anonymous design” — he cited the Jeep and a baseball glove as two examples — and he in turn inspired younger designers, like Naoto Fukasawa, Tom Dixon and Jasper Morrison.