Product Description

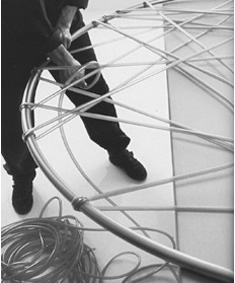

Fernando & Humberto Campana “Zig Zag” Screen 2001

Humberto Campana (1953 – ) Brazil

Fernando Campana (1961 – ) Brazil

Zig Zag Screen, 2001

Circular iron frame with electrostatic silver painted surface, translucent PVC hose stretched in a web pattern.

Illustrated: Campanas, Humberto and Fernando Campana (Sao Paulo: Bookmark 2003) p. 240; Mood River, February 3 – June 26, 2002, exh. cat. Jeffrey Kipnis and Annetta Massie (Ohio: Wexner Center, 2002)

H: 78” x D: 69”

Price: $11,500

Fernando & Humberto Campana “Zig Zag” Screen 2001

ALDO TURA Italy

Coffee table with furled edges c. 1950

Vellum-covered birch with mahogany lacquered cherry legs

Illustrated: Mid-Century Modern, Furniture of the 1950s, Cara Greenberg

(New York: Harmony Books, 1984) p. 160.

H: 18 1/2” x D: 21” x 37”

Price: $14,500

ALBERTO MARCONETTI Milan, Italy (active Argentina)

Armchairs (Two available) c. 1960’s

Oak, painted iron, leather strapwork and seat

Marks: by Alberto Marconetti (script signature)

H: 40 1/2” x W: 27” x D: 21”

Seat height: 19″

Price: $7,450 (each)

This pair of armchairs nods to the influence of such Italian designers as Carlo Bugatti and Carlo Mollino yet are their own unique creation. They have an unusual anthropomorphic quality in that the frame suggests a skeletal structure. In addition, the leather strapwork, iron loops and hooks allude to the equipage of the ancient Roman equestrian order.

SCHOOL OF MACKINTOSH (1868-1928) UK

Box with hinged cover c. 1900

Silver plate with a large abstract heart design and stylized Glasgow rose motifs in bas-relief.

Illustrated: Modern Silver throughout the world, 1880-1967, Graham Hughes (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1967), p. 145.

H: 2″ x W: 6 1/4″ x D: 4 3/4″

CHRISTOPHER DRESSER (1834-1904) UK

HEATH & MIDDLETON Birmingham, England

Petite claret jug 1887

Sterling silver mounts with hinged covers to both top and spout, glass, ebony handle

Marks: JTH & JHM in a four-lobed cartouche, London assay marks for 1887 (“M” in a shield), Vienna import mark (conjoined AV in a 6-sided cartouche)

Illustrated: Industrial Design Unikate Serienerzeugnisse, Die Neue Sammlung ein neuer Museumstyp des 20. Jahrhunderts, Hans Wichmann (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1985), p. 131; Christopher Dresser, ein Viktorianischer Designer, 1834-1904 (Cologne: Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln, 1981), p. 73, ill. 86, cat. no. 23; Industrial Design, John Heskett (New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 24, illus. 9; Christopher Dresser 1834-1904, Michael Collins (London: Camden Arts Centre, 1979), p. 171, cat.no.12.

H: 6” x Dia: 4”