Product Description

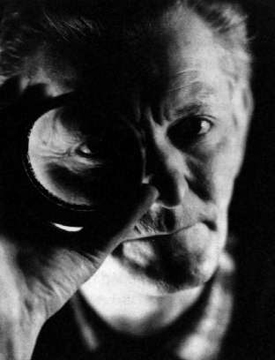

Edmund Kesting “Gears with hand” Photogram / Solarization c.1929

EDMUND KESTING (1882-1970) Germany

Gears with hand c.1929

Photogram / Solarization

Signed: Edmund Kesting 3644-280 (in pencil)

Provenance: Private Collection New York; Gene Prakapas Gallery New York 1970’s

Photogram: H: 7 9/16” x W: 6 15/16”

Frame: H: 15 9/16” x W: 14 15/16”

Price: $19,500

During the 1920s, Kesting was at the center of the avant-garde movement in Germany, where he befriended Kurt Schwitters and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. He first trained as a painter at the Akademie der Kunst in Dresden from 1911 to 1916. In the early 1920s, after service in World War I, he turned to collage and photography. An exhibitor at Herwarth Walden's Der Sturm gallery (Berlin), which supported German expressionism and the Blue Rider group, Kesting also operated several private art schools. The last, Der Weg (The Way), was closed by the Nazis in 1933. Kesting’s interest in the photographic portrait began in 1930, and often resulted in bold experimentation (Photomontages, superimpositions and solarizations) that provided some of the strongest examples of German expressionist portraiture in photography. In contrast to the objective naturalism of August Sander, his work is informed by the “Sturm und Drang” of the period – the storm and stress of the political, economic, and social unrest in Germany. After the war in 1948, Kesting taught at the Kunsthochschule in Berlin-Weissensee. – (partially excerpted from James Borcoman, Magicians of Light, National Gallery of Canada, 1993)

Works by Edmund Kesting can be found in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Solarization — is a phenomenon in photography in which the image recorded on a negative or on a photographic print is wholly or partially reversed in tone. Dark areas appear light or light areas appear dark. The term is synonymous with the Sabattier effect when referring to negatives, but is technically incorrect when used to refer to prints. In short, the mechanism is due to halogen ions released within the halide grain by exposure diffusing to the grain surface in amounts sufficient to destroy the latent image.

Edmund Kesting “Gears with hand” Photogram / Solarization c.1929

THOMAS F. BARROW (b. 1938) Kansas City, MO

Register Synthesis Photogram 1978

Gelatin silver print photogram with applied spray paint

Signed: Register Synthesis – 1978 – Thomas F. Barrow (in ink on back)

Exhibited: J.J. Brookings & Co. (San Jose, CA): Thomas F. Barrow: Inventories and Transformations, A Twenty Year Retrospective, Nov. 6 – Dec. 16, 1986. This exhibit occurred simultaneously with the following two museum shows: the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Nov. 6, 1986 – Jan 11, 1987) and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Feb. 26 – May 10, 1987).

Related photograph illustrated: Aperture: The New Vision: Forty Years of Photography, no. 87 (New York: Aperture Foundation, Inc., 1987), cover image.

Framed size: H: 19 5/8” x W: 23 7/16”

Thomas Barrow, American was born in Kansas City, Missouri. He studied at the Art Institute of Design in Chicago, Illinois and received his M.A. in 1967. At the George Eastman House, Barrow was the Assistant Director from 1971 to 1972 and served as the Associate Director of the University of New Mexico Art Museum from 1973 to 1976. Barrow started teaching photography in 1976 in the Art Department of the University of New Mexico and by 1985 he became the Acting Director of the University Art Museum. His Midwestern academic pedigree includes studying with Aaron Siskind at the Art Institute of Design in Chicago and with filmmaker Jack Ellis at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL. Barrow has received two NEA Photographers Fellowships in 1973 and 1978.

Barrow has produced a series of silver-gelatin photograms and then applied spray paint to the prints. These combine the feeling of a split-toned black and white print and at the same time appear as color-print photograms. He has produced a series of photograms entitled Disjunctive Forms. His images appear as surreal assemblages of various found and created objects superimposed with stencil text. Barrow works in the “academic” tradition—his pictures are deliberately and consistently experimental, highly intellectualized, scholarly in their concerns, and chock-full of references to the work of other artists.

GYÖRGY KEPES (1906-2001) Hungary/USA

Abstraction 1942

Silver gelatin print

Signed: Gyorgy Kepes 1942 (in ink on back)

Framed size: H: 18 13/16” x W: 16”

György Kepes was a Hungarian-born painter, designer, educator and art theorist. After emigrating to the U.S. in 1937, he taught design at the New Bauhaus (later the School of Design, then Institute of Design, then Illinois Institute of Design or IIT) in Chicago. In 1947 He founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he taught until his retirement in 1974.

DONALD DESKEY (1894-1989) USA

Papier-Abfälle c.1925-30

Provenance: The Estate of Donald Deskey

H: 9 7/8” x W: 7 15/16”

Framed: H: 22” x W: 18”

Donald Deskey was a native of Blue Earth, Minnesota. He studied architecture at the University of California, but did not follow that profession, becoming instead an artist and a pioneer in the field of Industrial design. In Paris he attended the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, which influenced his approach to design. He established a design consulting firm in New York City, and later the firm of Deskey-Vollmer (in partnership with Phillip Vollmer) which specialized in furniture and textile design. His designs in this era progressed from Art Deco to Streamline Moderne.

He first gained note as a designer when he created window displays for the Franklin Simon Department Store in Manhattan in 1926. In the 1930's, he won the competition to design the interiors for Radio City Music Hall. In the 1940's he started the graphic design firm Donald Deskey Associates and made some of the most recognizable icons of the day. He designed the Crest toothpaste packaging, as well as the Tide bullseye. His company is still in operation in Cincinnati. A collection of his work is held by the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. He is regarded the American pioneer of industrial design, and contemporary American graphic design.

GYÖRGY KEPES (1906-2001) Hungary/USA

Lens Refraction 1939

Signed: 6 (in a circle, on back); Gyorgy Kepes 1939 (in pencil on back)

Illustrated: New Bauhaus, 50 Jahre: Bauhausnachfolge in Chicago (Berlin: Bauhaus-Archiv and Argon Verlag GmbH: 1987), p. 185

Framed size: H: 27 1/8” x W: 22 ¼”

György Kepes was a Hungarian-born painter, designer, educator and art theorist. After emigrating to the U.S. in 1937, he taught design at the New Bauhaus (later the School of Design, then Institute of Design, then Illinois Institute of Design or IIT) in Chicago. In 1947 He founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he taught until his retirement in 1974.